Monzo’s Head of Data and Analytics walks through our recent advances using machine learning to make predictions based on existing data. The first section is an overview of what we’re using this for, and then we dive into the technical details with real-world examples.

When it comes to data science at Monzo, we have a lot more ideas than we can practically implement. In particular, with machine learning there are many promising business applications but it's prohibitively time consuming to test them all, especially as a small two-person team. Generally, before using a machine learning model you need to apply time-consuming manipulations to the data so that you can use it to train the model. If we could use the data we have in its raw form, we would be able to test many of these business applications for machine learning much more quickly.

Recently, we trialled a type of machine learning model called Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). RNNs specialise in making predictions based on a sequence of actions (known as an “event time series”), e.g. user logs in → taps on “money transfer” → encounters an error. The test results got me so excited about the potential applications of RNNs: all of our data is stored as event time series, so once we have implemented a RNN model to work with our data, we can apply this to almost any prediction problem at Monzo with minimal implementation time. I wanted to share a couple of the most interesting insights, as well as some conceptual implementation details.

We’re always working to build an amazing user experience and we would love to be able to preempt our users’ questions, and proactively answer them, even before they begin to write a message to the support team. Imagine if we could use the time series that documents users’ actions within our app, to do this. It sounds like science fiction, but in fact there is a lot of implicit information in the way customers navigate through the app before they get in touch with our customer support team to ask questions.

Using traditional methods, this type of information is difficult to make predictions from because it would require weeks of data analysis and manipulation. Even after weeks of work, we still might not be able to find interesting patterns.

In initial tests using RNNs on our users’ questions to customer support, we were able to correctly determine the question’s category in 30% of cases based on the preceding 200 events. We were additionally able to reach 53% accuracy when determining the top 3 potential categories, out of around 50 possible customer support categories.

In practice, this means that we could use this model to build a Help page that would instantaneously answer our users’ questions without them even needing to ask. Well, at least in 30-50% of the cases 😉 Then if you don’t get your answer immediately, there is still the option to start chatting with our customer support team.

Other use cases we tested

Besides predicting customers’ questions, another interesting RNN experiment we worked on was exploring how well the actions that customers take during signup can predict whether the account is fraudulent. We initially attempted to answer this question with more traditional data exploration techniques by constructing features manually and looking at correlations. This previous analysis failed as there was too much noise in the data and it was difficult to find time based patterns and deal effectively with the information contained in categorical variables. With the RNN approach, after tuning the model for a day we were able to detect 40% of fraudulent accounts with a corresponding false discovery rate of 42% purely based on onboarding events. This is only based on one of many signal types that we could use and we’d expect to be able to significantly improve this by using things like actual transaction events.

Now that we have built this framework to train RNN models based on our events data stream, we can test ideas like this within just one or two days. This is more than ten times quicker than manually designing signals.

What makes RNNs interesting from a technical perspective?

So, what makes RNNs so interesting from a technical point of view? Anyone who has built a predictive model before knows that it is pretty typical to spend 80% of your time engineering features that are predictive of the desired label. If you then also want to run the model in real-time you need to spend at least the same amount of time creating a data pipeline that calculates those metrics on the fly, depending on the complexity of the model. Wouldn’t it be great if we could remove those two time consuming steps? This is exactly what RNNs make possible — they require only the “raw” time series as an input, and they find relevant temporal signals automatically. A crucial benefit of taking events as input is that it is significantly less complicated to build a prediction pipeline that works in real time. The only thing you need to do for this is to persist the latest internal state vector of the used RNN cell in some way, e.g. by saving it in a database. This internal state vector is specific for every time series and can be interpreted as network’s memory of things that happened before. Once a new event for a given time series arrives, you can run the prediction by retrieving the state vector and “initialising” the network with it. No complicated data transformation pipelines required!

The strengths of RNNs also bring a significant disadvantage with them. It’s difficult to figure out the reasons behind any of the predictions that the models produce. In some cases this isn’t an issue, like when we are predicting customer questions, but in cases like fraud detection we can’t rely on black box models alone. That is because we need to be able to justify the decisions we are taking, in particular if the decision involves closing someone’s account. There are a few techniques which we can use to work around those interpretability limitations. Here is a great in-depth article that you should take a look at if you want to know more. A good solution for the fraud detection use case is to not use one big model that takes everything as an input, but rather try to train an ensemble of small and interpretable models. Another promising approach would be to use an Attention Mechanism which became popular in Natural Language Processing (NLP) applications in the last two years.

Conceptual implementation

RNNs have been around for a while now but came into the spotlight again in recent years due to numerous state of the art research results in Natural Language Processing (NLP) applications. RNNs are usually applied to text in NLP, or to purely numerical time series, as they are very well suited to capture the positional/temporal patterns. There are a lot of amazing blogs out there that describe how RNNs work and how to implement them using a standard deep learning library like Tensorflow. Here is an RNN code example in TFLearn which is especially suitable for people who are new to RNNs. In our case, we used a plain vanilla stacked RNN with a GRU cell, dropout and L2 regularisation. In the example below, we are going to skip over the theory and implementation of RNNs and rather focus on the practical aspects of how to make your events data suitable as model input. To accomplish this we have borrowed the concept of word embeddings from NLP research which became a standard practice over the last several years.

Here is what a typical event looks like in our analytics pipeline. It usually has a mixture of categorical and numerical properties and the majority of data is in a semi-structured JSON blob. Some of the categorical properties, like “merchant” below, might have thousands of unique entries which we would like to be able to use in our models.

| timestamp | event_name | payload |

|---|---|---|

| 2017-04-25 07:40:02 UTC | user.signup | {source":"Facebook", "age": 31, "user_id": 123, ...} |

| 2017-04-25 07:51:02 UTC | transaction | {"merchant": "Ozone Coffee", "user_id": 123, ...} |

To be able to feed it into the RNN layer we need to transform this event into a purely numerical form, i.e. N-dimensional vector. This numerical representation vector should have the same dimension N for every event in every time series.

We can achieve this in three steps. First, we bring the JSON payload into a tabular format:

| timestamp | event_name | source | age | merchant | user_id |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017-04-25 07:40:02 UTC | user.signup | 31 | NA | 123 | |

| 2017-04-25 07:51:02 UTC | transaction | NA | NA | Ozone Coffee | 123 |

Second, words are mapped to IDs. There are existing libraries that let you easily do this e.g. TFLearn’s VocabularyProcessor data utility.

| hour | day_of_week | mins_since_prev | event_name | source | age | merchant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 2 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 | 31 | 0 |

| 7 | 2 | 11.0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

Note, every column has a separate ID domain and we don’t use the raw timestamps as an input. Instead we derive a few metrics from it, e.g. hour, day of week and time since previous event. This form above is how you would feed the data into the network’s input layers — however not as one vector of IDs but instead using each column as a separate vector, because you will want to learn separate embeddings for each of your categorical features in the next step.

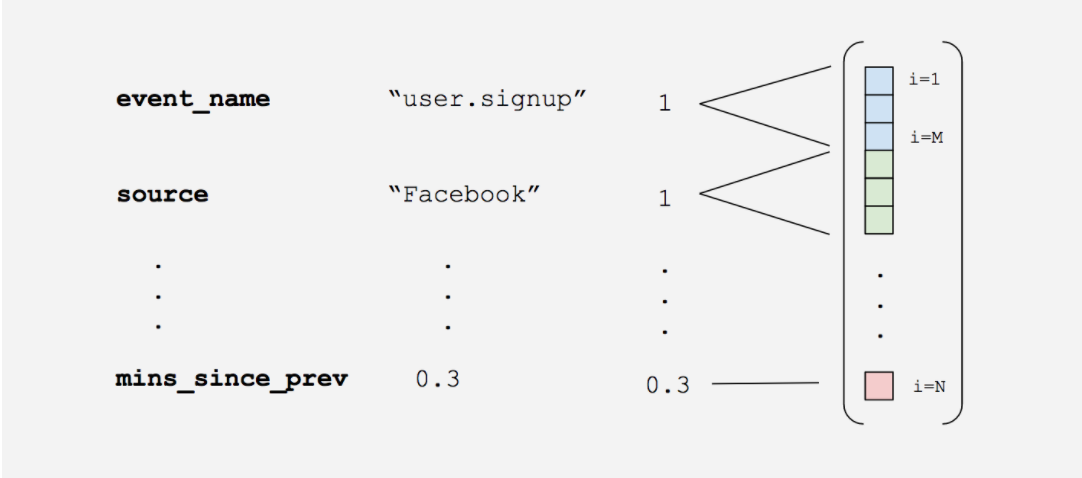

Finally, we embed the categorical input IDs which means that we represent every ID as an M-dimensional vector.

This representation is learned by the network itself and we don’t need to provide this embedding function. Why do we need word embeddings instead of feeding 1-hot encoded words into the RNN layer? Imagine you have >10k merchants. This would result in >10k dimensional vectors that feed into the RNN layer and would also translate into an order of magnitude more parameters to estimate. This might work in theory, but it would require more training data and would be computationally more expensive. In more technical terms, word embeddings are distributed representations which act as strong regularisers.

What about the labels? What are we actually predicting? This is a part that is very application specific. In the two use cases we have trialled, the prediction label was applied to the whole user time series. e.g. when predicting the next issue a customer will contact us about, we took 200 events prior to the contact event and tried to predict the issue type purely based on those events. So when using the described model, we are predicting the most likely issue the customer is facing at any given point in time — we are not predicting the actual “contact” event. There is also a way to use RNNs to make a “time to event” type of prediction. Here is a very insightful post on this topic.

Final thoughts

With microservices becoming ever more popular, there are more and more startups using event driven architectures for analytics. If you are a Data Scientist or an Engineer in such a company and are interested in exploring new machine learning approaches, RNNs might be one of the most interesting avenues to explore. Building a general model once will enable you to test numerous ideas in a surprisingly short frame of time.

If you’re excited by what we are doing and want to help us building cutting-edge data infrastructure, come and join our team as a Data Engineer!

I hope this post provokes some thoughts and provides some inspiration to those of you who are thinking about similar problems. Let me know what you think via Twitter @dimitrimasin or our community forum.