Last month we crowdfunded £20 million from 36,000 investors. After the round opened to new investors at 10am on the 5th December, we reached our goal in less than three hours! We ran the investment round on our own platform, with a native in-app flow we built from scratch. We hosted it on our microservices architecture written in Go and managed by Kubernetes, which all runs on Amazon Web Services. This is the same technology stack we use to run our bank, which we’ve also built from the ground up.

Overall, the round went smoothly and nothing on our platform crashed. To get us to that stage, teams across the company coordinated their efforts for several months. We architected and built a scalable investing backend that would serve investments quickly and cope with the demand we expected.

We decided to crowdfund £20 million

In mid-2018, we decided to raise £20 million from our customers as part of our next investment round.

Crowdfunding isn’t new to us – we’ve done it a few times before. Our round in 2016 crashed our partner’s servers. For our 2017 round, we built a ballot that let people pledge investments, and we randomly selected investors later. This was complicated to run and meant that a lot of people missed out on investing.

The lessons we learned from previous showed we needed a better system, one which:

Gave everyone an equal chance to invest

Could handle the investment traffic we expected

Wouldn’t crash our bank if things went wrong

We weighed up our options

We carefully considered the risks and benefits of each approach for a few weeks, discussing with various teams to make sure what we decided to build was achievable and everyone was on board. We held a meeting with lead engineers from our product, platform, payments, financial crime and security teams for a final go/no-go decision.

Use a partner’s platform

Like in previous rounds, we could have asked people to invest through a partner's platform. But we didn’t want to risk bringing someone else's platform down again, which would affect our round and all the other companies raising money.

Run a ballot system

We could try and run a ballot system and select investors randomly again. But we didn’t want people to miss out.

From a technical point of view, building a ballot for a £2.5 million round was complicated enough. For a £20 million round, this would be even more complex.

Invest through a web page

We could have built an investment page on monzo.com and taken investments through there. But we’d need to confirm that investors were also Monzo customers.

According to English law, a private company like Monzo isn’t allowed to offer shares in itself to the public. In previous crowdfunding rounds, investors were only able to invest because they were registered users of the Crowdcube platform (a defined and limited group of people). If we wanted to offer the shares directly, we’d need to clearly define a group of people who’d be eligible to invest. We could limit the offer to people who were Monzo customers, but we’d need a way to verify that.

We could do that by asking everyone to log into their Monzo account online. But because we use magic link e-mails instead of passwords to log you in, the sudden rush of people requesting magic links could cause major e-mail delivery issues. It could even bring down our authentication system, which would break the Monzo app for everyone!

Invest through the app

Giving people the option to invest in-app fixes the login issue: most Monzo users are already logged into the app and most active users wouldn’t need to refresh any tokens.

Investing in-app would also create the smoothest user experience: a custom-designed, native flow where the money could come directly out of your account at the end without inputting any extra details.

So we chose to go ahead and start building the option to invest through the app, and the backend to support it.

Architecting the system

Engineering projects at Monzo often start with a “Proposal”: a document that explains the requirements and risks of a potential project, that we share with relevant teams and the whole company for feedback. If they’re accepted, they become the defining technical document that we use to implement the system.

Crowdfunding in-app would involve collaborating between teams across the company – from payments, platform and product, to financial crime and security. So we worked together to create a proposal. The document outlined:

What we wanted to achieve by building crowdfunding in-app

The risks and challenges

How we would architect the backend to address those risks and challenges

There were four constraints we had to work within:

We’d have to cope with lots of traffic

We couldn’t raise any more than £20 million

Users need to have enough money available to make the investment

We mustn’t bring down the bank

1. We’d have to cope with lots of traffic

People would be investing on a first come, first served basis, so we expected most people to show up as soon as the round opened. None of us knew exactly how many people would decide to invest in the first few minutes of the round, but we could extrapolate from previous rounds to come up with a few best guesses.

For example:

In 2016, we raised £1 million in 96 seconds

What would happen if enough people wanted to invest at as soon as the round opened that we reached our £20 million goal in a few minutes?

If the average investment size was £500 (roughly the same as the last round), that would mean 40,000 investors in less than 2 minutes

If the average investment was lower but we had more people investing overall, that would mean even more investors and even more traffic

To account for the most extreme scenario, we decided to prepare for up to 100,000 investments in as little as 5 minutes, with a sharp peak of 1,000 investments per second in the first minute or so.

On a normal day, somewhere between 10-20 people open their Monzo app every second. According to our estimates, we’d need to prepare for over 300 people per second, or 15-30 times the average load. We’ll explain in another blog post how we prepared our platform and optimised the Monzo app to cope.

But for architecting the investment systems, it was clear we needed something that could handle at least several hundred people per second trying to invest at the same time, probably with an initial spike that went even higher.

For a customer to invest, we needed to move money out of a their account, into a Monzo investment account. For this to happen, we need to record both movements of money in something called a ledger:

The outgoing payment from a users’ account as a negative

The incoming payment to our investment account as positive

We were adamant that crowdfunding shouldn’t interfere with anyone’s payments, and the only way to do that was to remove the movement of money out of the critical path of investing. So we decided to build a two-tiered system consisting of:

A “pre-investment” layer, which would be able to handle extremely high levels of load and let potential investors know quickly whether or not they were able to invest

A final investment layer, which would asynchronously move the money and complete the investment in the background

2. We couldn’t raise any more than £20 million

We couldn’t accept investments that totalled more than £20 million – the number we agreed with the institutional investors leading the funding round.

But because we were expecting a lot of people to invest very quickly, making sure that we didn’t go over the £20 million limit posed a challenge. We needed to find a way to keep track of the total amount people had invested very accurately, even though lots of people were investing in a very short period of time.

Some feasible ways of doing this:

a. Sum the current investments each time

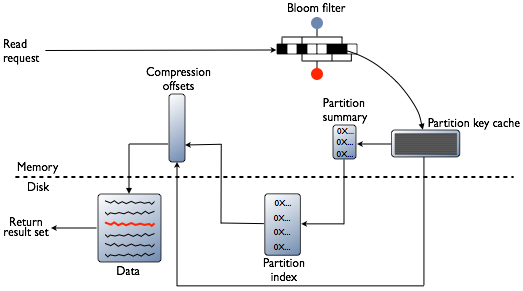

We use Cassandra as our main database, mainly because of it’s horizontally scalable and fault tolerant. Cassandra is designed for high write throughput, where writes are appended to a Memtable and commit log, then flushed to disk to an “SSTable”. They require no disk reads or seeks. On the other hand, reads require potentially multiple disk seeks as the data might exist across multiple SSTables.

Here is the typical path Cassandra follows for a read request:

Reading all the current investments under a lock and summing them up was probably going to be too slow to be in the critical path of investments.

b. Storing the count as a Cassandra counter

Cassandra is a distributed data store and atomic counters aren’t exactly its bread and butter. There is a counter data type, but it comes with a warning:

Tracking count in a distributed database presents an interesting challenge. In Cassandra at any given moment, the counter value may be stored in the Memtable, commit log, and/or one or more SSTables. Replication between nodes can cause consistency issues in certain edge cases.

We’ve experienced problems with counters before. Once, we even found a bug in the Cassandra source code that prevented some of our services that use a counter from starting correctly. So we decided we didn’t want to rely on this to serve as the investment counter.

c. Store the count in a different database

We could have used another database with support for reliable transactional updates to a counter row. But the operational complexity and risk of introducing a new database to our platform and architecture for a single value would’ve been significant. We didn’t want to do this unless the tools we use day-to-day didn’t offer another way.

d. Store the count in memory with a “watermark” flushed to disk

Storing in memory is an obvious solution for cheaply reading and atomically incrementing a count. The problem is resiliency. If the service storing the counter crashes and restarts, the counter needs to be re-populated from disk. The service storing the counter would also have to boot up very quickly to recover from any crash, so in a failure scenario the investments wouldn’t be interrupted for too long. For this reason it wouldn’t be desirable to initialise the counter by reading all the investments: it would mean reading up to 100,000 investment rows from Cassandra at a time of high load.

Instead, we could periodically flush the count to a consistent data store using a timestamped “watermark” value. On restart, the service would then populate its counter by reading this single watermark value, then reading the investments made since the recorded timestamp and adding them to the total. If the service had to restart, this would drastically reduce the number of rows it would have to read from Cassandra. With a few things to be careful about (for example clock-skew between two spawned instances of the counter service), this seemed like a very fast and robust solution.

We chose option four as it gave us the best balance of speed and consistency. We stored and incremented the total investment count in a crowdfunding-total service in-memory, making use of Go’s atomic package. We then flushed the total invested every second to etcd which is a distributed key/value store we already use as part of Kubernetes.

3. Users need to have enough money available to make the investment

Working out how much money a user has is similarly expensive to figuring out the total amount invested, and involves reading from a ledger. So we wanted to avoid doing this calculation in the critical path of investments. But the ledger is also the only fully-consistent view of the real balance of an account, so we still have to read at some point before moving money out of the user’s account. We can’t rely on cached values for moving money.

We resolved this dilemma by splitting the investment system’s design into two:

A “pre-investment” stage which relies on a cached view of the world to record or reject the investment as quickly and efficiently as possible. The accepted investments would be put onto an async queue (we used NSQ for this) for processing.

An “investment” layer which runs all the expensive operations and checks, before accepting the investment and moving money. This step processes tasks asynchronously from the pre-investment queue.

The pre-investment stage used the user’s cached account balance (which we've been storing in a balance service for a while) to do an “approximate” check. This balance also lends itself well to being cached in-memory, so we introduced an in-memory LRU balance-cache to do the approximate check without hitting Cassandra the majority of the time.

This two-tiered design not only helped us check account balances quickly, but also gave us much more control over how we let actual investments through.

4. We mustn’t bring down the bank

Crowdfunding shouldn’t cause issues or bring down the bank for everyone else.

We run distributed, multi-replicated and resilient systems by default as part of our modern bank backend. But there are still key systems (like Cassandra and etcd) that aren’t trivial to reactively scale to handle massive surges in demand. If we tried to process investments in real-time, there was a high risk that we’d affect the processing of payments that weren’t related to crowdfunding.

Using caching and the two-stage investments system let us remove Cassandra reads from the pre-investment path altogether. This gave us great confidence that we wouldn’t overload critical components of our infrastructure, even if tens of thousands of investors all showed up at 10am.

There were some small caveats. For example, it was possible to have rare race-conditions where a user could get a “success” message after investing, but have their investment declined later because they didn’t have enough money. But overall this was a much better alternative to risking issues with other payments.

The final architecture

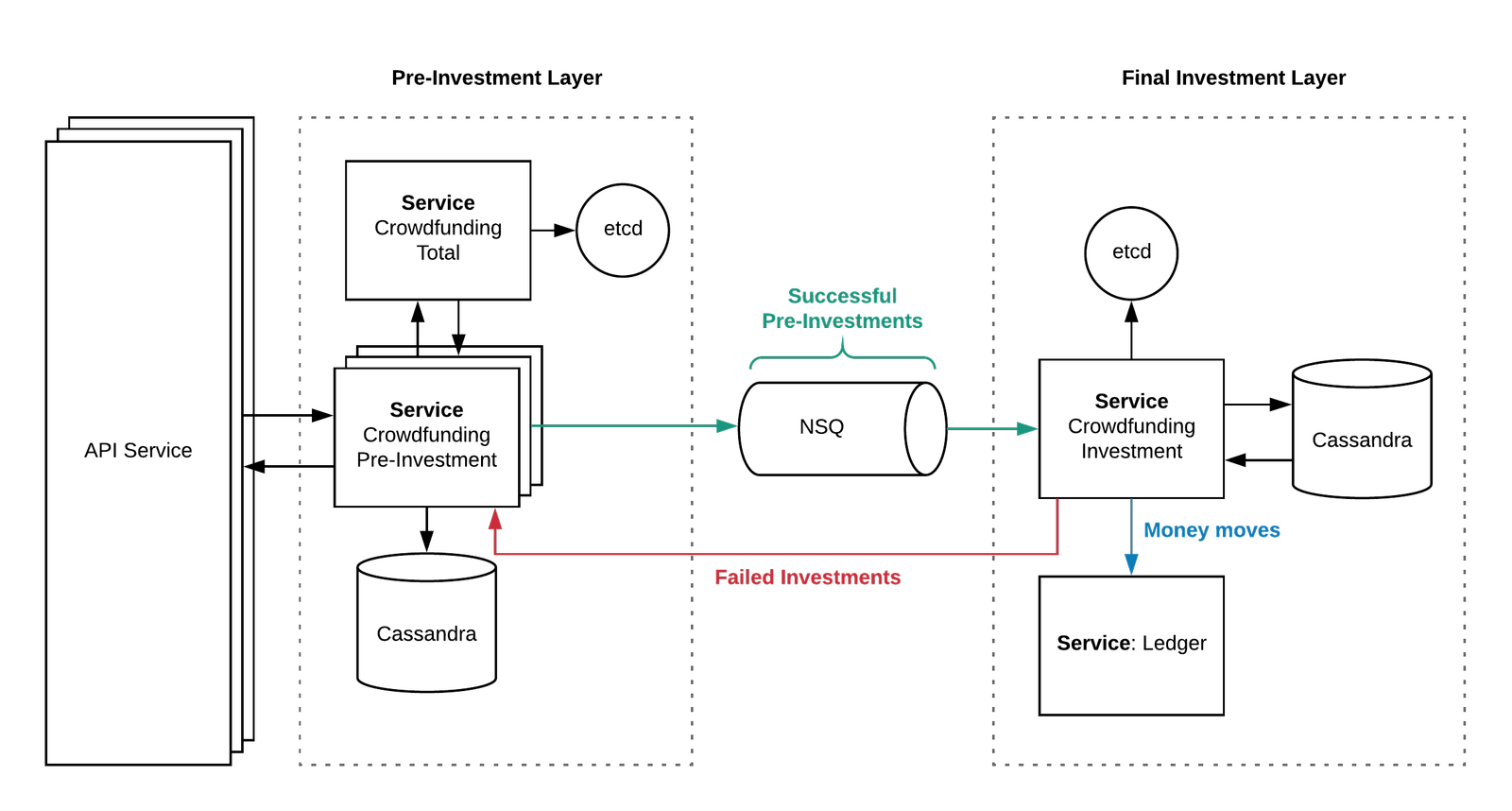

Here’s what our final architecture looked like:

The pre-investment layer

An API service which exposed a JSON API to our apps to be able to initiate and read investments.

A singleton

crowdfunding-totalservice that kept track of the total invested amount and which users have already invested in memory. It flushed the total invested to etcd every second to quickly be able to cope with restarts without having to re-compute the entire total from Cassandra.A

crowdfunding-pre-investmentservice to handle investment requests from the API and checkedcrowdfunding-totalto accept or reject a given investment.Successful investments are written to Cassandra, then published onto a dedicated NSQ cluster and topic to be processed asynchronously by the final investment layer.

Failed investments are written to Cassandra, and a failure is passed down to the user.

The final investment layer

A singleton

crowdfunding-investmentsubscribes to the investments NSQ topic and consumes them one by one with a rate-limiter of around ~60 per second. For each user, it acquires a lock and does some final checks, including:Does the user have enough money?

Is the user eligible to invest?

Have we hit the £20 million investment goal?

If any of the above checks don’t pass, the crowdfunding-pre-investment is called via an RPC to mark the failure and inform the user.

The Ledger service, which is the same ledger we use for the rest of the bank, records two entries denoting the money coming out of the user’s account and entering Monzo’s investment account.

Various asynchronous services downstream of the ledger that make sure the user sees an investment item in their transaction feed in the Monzo app, gets a notification, gets marked as an investor so they can receive a “Monzo investor” card, and so on.

Here’s a simplified graphic of how the final architecture looked:

Did it work?

In a word, yes! The investments started pouring in a few seconds after 10am. We experienced peak load between 10:01 and 10:03, raising over £4 million in less than two minutes, and almost £7 million in the first five.

While it wasn’t quite the £20 million in five minutes we prepared our backend for, it was good too see that our guesses weren’t wildly unrealistic. It’s also four times the peak load of our 2016 crowdfunding round! You can see more stats and graphs about the round in this blog post.

With an engineering project this large, it’s hard to get the architecture and preparation exactly right. At times we thought we might be over-engineering things. At other times (especially during load testing) we felt our platform might struggle keep up with the expected peak demand. But thanks to our level preparation, we raised the money smoothly and nothing went down.