A few weeks ago, we launched our new machine learning powered help screen and since then, more than 40,000 questions have been asked through it. In this blog post, I want to present a more technical explanation of how the model works and explain exactly what’s happening behind the scenes.

The Challenges

We didn’t have any existing search data to train on

To train machine learning models, we’d normally need training data that maps exactly to the task at hand. For instance, to train a machine learning model to recognise cats, we’d probably feed it lots of cat and non-cat images to let the model learn how to differentiate between the two. However, we didn’t really have any search data because it wasn’t a feature in the app yet!

Classic information retrieval ranking techniques gave us subpar results

We experimented with probabilistic techniques like BM25 and tf-idf by building a simple search engine to retrieve similar questions. But because these algorithms essentially rely on keyword matching, and because a lot of our questions are relatively short in length, they didn’t work reliably.

Unstructured natural language data

Text is a form of unstructured data that can’t be fed into an algorithm directly. Compounded with the fact that natural language is nuanced and subjective, the problem becomes much more difficult to solve. The same question can be phrased in many different ways: if a user realises they have been double charged, the question could take any of the following forms:

±Help, I’ve been double charged!

I was having brunch this morning at a restaurant in New York. Does your card work there? I see two outgoing transactions for the same restaurant.

I think my card may have been cloned - my balance is deducted twice! But I only went to McDonalds once. What kind of monster is McDonalds they charge twice in one day?

Examples like these show that natural language questions can be vague, full of irrelevant words, or just have multiple ways of phrasing the exact same question. This makes coming up with manual rules to classify questions intractable.

Solution

At this point we knew we’d need some sort of machine learning system and that we’d have to train the model not on a search task, but a natural language task related to search. We knew we had lots of customer service questions and answers from our existing in-app chat so thought,

By training a model on all our previously seen customer support data, we managed to make a model ‘understand’ natural language, at least in the highly narrow domain of Monzo’s customer support queries.

(Somewhat) technical details

Overview of training methodology

Given a sentence of length η, we want to find an encoding function

f that encodes it into vector $$\vec{x}$$:$$\vec{x} = f(w_1, w_2, w_3, ... w_n)$$ where $$w_i$$ are the word vectors corresponding to the words in that sentence.

The goal is approximate a function $$f()$$ using empirical data. We define the action of converting a sentence into words as encoding, and the corresponding network as the encoder.

We referred to Feng et. al (2015) to structure our training mechanism:

During training, for each training question Q there is a positive answer $$A^+$$(the ground truth). A training instance is constructed by pairing this $$A^+$$ with a negative answer $$A^-$$ (a wrong answer) sampled from the whole answer space. The deep learning framework generates vector representations for the question and the two candidates: $$V_Q,V{A^+},V{A^-}$$. The cosine similarities $$cos(V_Q, V{A^+})$$ and $$cos(VQ, V{A^-})$$ are calculated._

Like the authors of the paper, we then used a hinge loss function to train the algorithm: $$L = max{0, m - cos(VQ, V{A^+}) + cos(VQ, V{A^-})}$$ where $$m$$ is the margin, which we set to 0.2.

By optimizing this loss function, we’re able to make a question and correct answer pair have high cosine similarity, and a question and wrong answer pair have low cosine similarity. This training approach allows us to get past the problem of the lack of data, since we don’t need explicitly labeled examples - just the question and answer pairs which we already have. To make training more efficient, after every few epochs, we shuffle the dataset so that the model always sees “semi-hard” triplets, an idea we got from Google’s Facenet paper.

We used Adam as our optimizer and then threw some GPUs at it until the problem surrendered - Isn’t that how deep learning is done nowadays?!

Encoder architecture

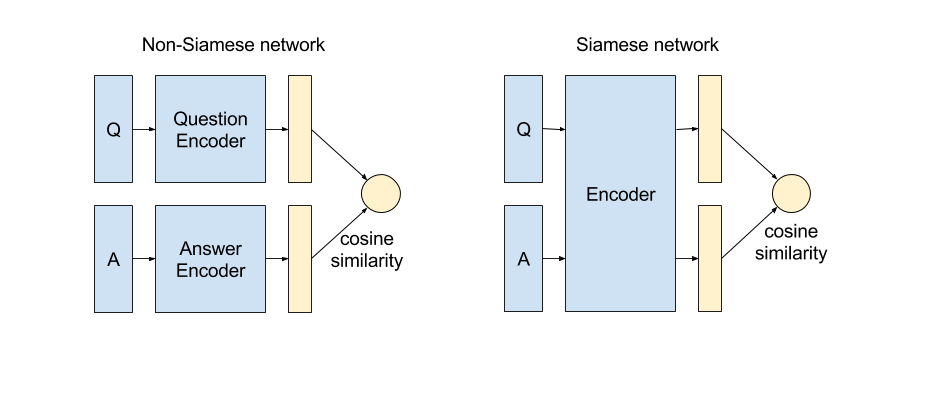

Now that we have our training structure in place, it’s time to choose the architecture for the encoder. After a long series of trial and error (trust me this was a pretty dark time in my life), we went with a hierarchical attention subnetwork within a Siamese network.

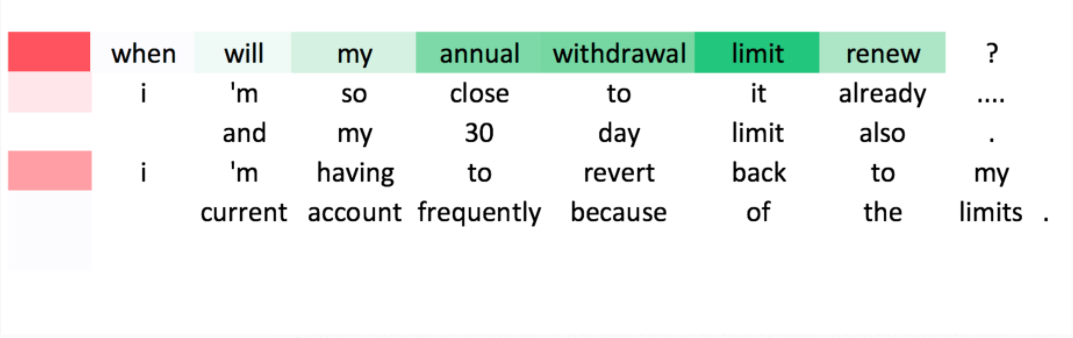

Based on our experiments, we discovered that a network with attention outperforms one without, which fits our intuition - lots of customer support queries are rife with irrelevant words, email/text signatures, salutations etc. One cool feature is that by visualising the attention, we can see that the model is able to correctly pick out important words:

Model picks out the 1st sentence as most important. And the words ‘annual withdrawal limit renew’ as the most important words in that sentence. This is consistent to what our COps team would do.

A Siamese network is essentially a network that uses two or more identical subnetworks. This helps training converge faster, since we basically halve the number of trainable parameters, while sharing the same parameters also acts as a regularizer. As a bonus, it makes serving easier as well - instead of saving two separate networks, one for question and another for answer, we just have one network that can be used to encode either.

Serving

During serving time, we only have to conduct the feedforward process on 1 datapoint - the user’s input query. All the vectors for answers are precomputed and saved as a binary file as a numpy matrix. The only thing left to do is compute cosine distances of the query to the 50+ answer vectors. This makes the computation part of the serving process relatively simple. With every incoming query, we display the top-5 closest help topics in terms of cosine distance. Another great part about a ranking-based model architecture is that we can always add new answers at will without retraining the model.

We used Keras during training time, but when serving the model, we froze the Keras model into a Tensorflow protobuf. We found this reduced the size of our model by 50% because tensorflow intelligently freezes only the part of the network we needed, and it also removes all unnecessary metadata required only for training. The result is a binary that contains everything from model weights to word vectors. This freezing of the model is especially useful if you have CPU/RAM constraints when serving (which we do due to our microservice architecture).

We serve the model as a REST API with Flask behind a gunicorn server. This is then Dockerized and then put into production as a microservice on our Kubernetes cluster. This last sentence alone has enough buzzwords to get me a job at any hip startup with a ping pong table.

Why didn’t we use tensorflow serving? Honestly, the only reason is familiarity with the Flask framework. I feel Flask works well enough for our simple use case. TF serving is probably more optimized for serving machine learning models, but also comes with a lot more functionality which we don’t need. This is definitely something on my to-learn list though. Sidenote: I’d like to see a comparison of serving a model with Flask/Django + webserver vs. tensorflow serving. There aren’t enough resources/benchmarks on deploying machine learning models out there.

A couple other things we tried but didn’t work

We tried various combinations of CNNs, bidirectional RNNs and residual connections. All these gave varying results but we found hierarchical attention to be one of the best performers. We also tried a different training architecture and loss function where instead of using the margin hinge loss function, we use binary labels, where a (Q, A+) pair is labeled 1, while a (Q, A-) pair is labeled 0, and then trained with a binary cross-entropy loss function (log loss). This didn’t work as well as hinge loss — perhaps the shape of a margin-based loss function is more suited for ranking.

Honestly I could have kept trying and spent the rest of my youth tweaking it to squeeze out that extra 0.1%, but who has time for that?

We also didn’t start with using deep learning straightaway. We conducted experiments with basic textual models like Naive Bayes and linear SVMs using a bag of words approach, but the results weren’t as good as deep learning based models.

Conclusion

So there you have it, the magic behind our help search algorithm! This problem was an interesting one because it wasn’t a straightforward classification problem, unlike most machine learning projects. This is the first data science product within the Monzo app and we hope there will be many more to come!